By Lucy Coatman

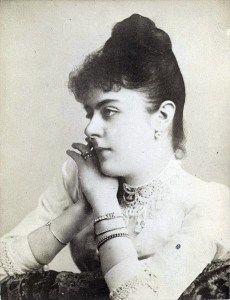

Cover Image: Crown Princess Stéphanie, mid-1890s, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St%C3%A9phanie,_Crown_Princess_of_Austria-Hungary.jpg

‘Dear Stéphanie,

You are freed from the torment of my presence. Be happy in your own way. Be good to our poor daughter, who is all that is left of me. […] I face death calmly, death alone can save my good name.

With warmest love from

Your affectionate Rudolf.’

Stéphanie, Crown Princess of Austria, felt these words like a ‘dagger thrust’ in her heart.[1] Her husband, Rudolf, had been found dead at Mayerling hunting lodge alongside his seventeen-year-old mistress, Baroness Mary Vetsera, in the early hours of January 30th, 1889. By taking his own life, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne had shaken not only the Empire. The life of the woman he left behind would never be the same.

Born in Brussels in 1864, Stéphanie was Princess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and Duchess in Saxony. Her parents’ marriage was not a happy one, and Stéphanie’s childhood was rather harsh.

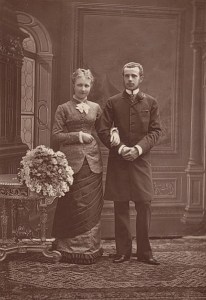

In 1880, the young Belgian princess became engaged to Rudolf. Writing many years later in her memoirs, Stéphanie described herself as a fifteen-year-old anxious to please: ‘Should I be capable for meeting the demands which would be made upon me[?…] Was I to bind myself forever to a man whom I did not even know?’[2] The apprehension about what lay before her is palpable many years later. The wedding in Vienna was set for February 1881 but was delayed as Stéphanie had not yet begun to menstruate. This fact would have been more embarrassing for the Crown-Princess-to-be and her current and future families than we could probably comprehend today.

The marriage began rockily. Rudolf took one of his mistresses along to Belgium for the engagement and Rudolf’s mother, the judgemental Empress Elisabeth, was unimpressed with her future daughter-in-law. Their relationship was never warm, and Stéphanie often had to stand in for the restless and absent Empress at court functions, later writing ‘I had no rest, and was obliged to appear at all ceremonies, now here, now there! We [Stéphanie and Rudolf] had continually to show ourselves, smile, converse, hold receptions, accept invitations, attend festivals and theatrical performances.’[3]

The couple’s first night alone signified how their relationship was to continue. Later, Stéphanie wrote of the awkwardness between the young couple and the disappointment of the cold, unwelcoming atmosphere when they reached Laxenburg Palace, outside Vienna. Once there, not knowing what awaited her, Rudolf treated Stéphanie brutally on their wedding night. Retrospectively, she wrote ‘what a night! What torments, what horror! I had not had the ghost of a notion of what lay before me, but had been led to the altar as an ignorant child. My illusions, my youthful dreams, were shattered. I thought I should die of my disillusionment.’[4]

Unable to find fulfilment in her marriage, Stéphanie immersed herself in the role of Crown Princess, undertaking these duties earnestly. She also hoped that the coming of a child would bring about affection between the couple. Their relations certainly improved during her pregnancy, but disappointment struck again: they had a daughter, Elisabeth (known as ‘Erzsi’). As Rudolf then infected Stéphanie with a venereal disease, Erzsi was to be their only child.

The couple grew increasingly distant and, in 1887, Stéphanie discreetly took a lover of her own: Count Artur Potocki. Despite the emotional and often physical distance between the royal couple, Stéphanie noticed in October 1888 that Rudolf was in a frightful state of ‘internal dissolution,’ and she spoke of her worries to Emperor Franz Joseph, who dismissed her fears. Just a few months later, her husband shot both himself and his young mistress at Mayerling.

Despite being Rudolf’s wife, Stéphanie was one of the last to find out the dreadful news, a fact which she bitterly recalled in her memoirs.[5] Stéphanie also wrote that she was in a state of inward collapse, despite the cool exterior noticed by those around her, such as Archduchess Marie Valerie (Rudolf’s younger sister).[6] Despite the couple’s coolness in life, Rudolf’s death was nevertheless an incredibly hard blow for his 24-year-old widow, who faced its consequences for the rest of her life.

The relationship with Artur Potocki continued after Rudolf’s death. Stéphanie truly loved him and felt his loss when he died a little over a year after Rudolf; “I have lost my best friend,” she wrote to her sister Louise.[7] Her life in Vienna was only to get harder; she was Dowager Crown Princess, but she had no purpose at court. She was refused permission to visit home and forced to reject an invitation from Queen Victoria.[8] She was, however, able to travel in Habsburg lands, and spent her days taking painting and dance lessons, as well as attending and opening concerts and events.[9] The Empress scorned Stéphanie, feeling a large part of the blame for Rudolf’s death lay on her daughter-in-law’s shoulders. Happiness came when she married a Protestant man of lower status, Count Elemér Lónyay in 1900, though it came at the expense of a break with her Belgian family. Additionally, she lost her role at court, and Emperor Franz Joseph took on the guardianship of her only child. But finally, she was free to love and live in peace.

Her daughter, who was a source of great comfort to Stéphanie after Rudolf’s death, was soon to leave her affections. The mother-daughter relationship became tense after Stéphanie’s second marriage due to Erzsi’s growing devotion to her dead father.[10] Stéphanie returned her daughter’s cool feelings by disinheriting her.[11] Stéphanie’s memoirs were published in 1935 and were considered scandalous. They were censored in Austria and even led to a court case with Erzsi. Stéphanie died in 1945 at the age of 81, shortly after the Soviet arrival in Hungary, and is buried beside the beloved husband to whom her memoirs are dedicated.

Stéphanie is not the only woman who had to live with the repercussions of Mayerling. Rudolf’s mother, Empress Elisabeth, entered lifelong mourning. You can read about this later this month.

Further Reading

H.RH. Princess Stéphanie of Belgium, I Was To Be Empress, London: Ivor Nicholson & Watson, 1937.

Lucy Coatman, Love Is Dead: Newly discovered letters get us closer to understanding the tragic truth of royal murder-suicide at Mayerling, History Today, February 2022).

Brigitte Hamann, Rudolf: Crown Prince and Rebel, trans. Edith Borchardt, New York: Peter Lang, 2017.

Brigitte Hamann, The Reluctant Empress, trans. Ruth Hein, London: Faber and Faber, 2010.

Georg Markus, Katrin Unterreiner, Das Original-Mayerling-Protokoll der Helene Vetsera, Vienna: Amalthea, 2014.

Rudolf R. Novak, Das Mayerling Netz, Vienna: Berger Horn, 2019.

You can find out more about Lucy’s work here: Twitter: lucy_coatman, Instagram: lucycoatman

[1] H.RH. Princess Stéphanie of Belgium, I Was To Be Empress (London: Ivor Nicholson & Watson, 1937), 248.

[2] Princess Stéphanie, I Was To Be Empress, 91.

[3] Princess Stéphanie, I Was To Be Empress, 129.

[4] Princess Stéphanie, I Was To Be Empress, 113.

[5] Princess Stéphanie, I Was To Be Empress, 247.

[6] Marie Valerie of Austria, Das Tagebuch der Lieblingstochter von Kaiserin Elisabeth (Munich: Piper, 2016), 172.

[7] Quoted in Friedrich Weissensteiner, Frauen um Kronprinz Rudolf (Vienna: Kremayr & Scheriau, 2004), 166.

[8] Princess Stéphanie, I Was To Be Empress, 254.

[9] Weissensteiner, Kronprinz Rudolf, 179.

[10] Friedrich Weissensteiner, Die rote Erzherzogin (Vienna: Piper, 2007), 138.

[11] Weissensteiner, Die rote Erzherzogin, 138.

One thought on “Stéphanie: A Life in the Shadow of Mayerling”